The article summarizes the carbon market, including carbon credits, its history, and greenhouse gas reduction projects. It explains both compliance and voluntary carbon markets, and their current implementation worldwide. Vietnam faces challenges without a domestic carbon market, affecting its competitiveness and sustainable development. The benefits of carbon pricing tools for governments, businesses, and investors are highlighted. To address these challenges, developing a robust domestic carbon market and aligning regulations with international standards are essential. The overall message emphasizes the significance of establishing a domestic carbon market for Vietnam's future progress.

I. Context and Current Implementation of the Mechanism Worldwide

I. Context and Current Implementation of the Mechanism Worldwide

What is a Carbon Credit?

Carbon credit is a general term for tradable certificates or permits representing 1 ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) or the equivalent mass of another greenhouse gas, measured as 1 ton of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e). The buying and selling of CO2 emissions or carbon in the market are conducted through these credits.

The History of Carbon Market Development:

The carbon market originates from the United Nations' Kyoto Protocol on climate change, which was adopted in 1997. According to the Kyoto Protocol, countries with excess emissions allowances can sell to or buy from countries with emission targets. Consequently, a new commodity emerged worldwide in the form of emission reduction/removal certificates. Since carbon (CO2) is the equivalent conversion of all greenhouse gasses, these transactions are collectively referred to as carbon trading, carbon exchange, or the formation of the carbon market or carbon credits market.

Common Carbon Reduction Projects

Carbon reduction projects are commonly categorized into two types: nature-based and technology-based. Nature-based projects typically include reforestation, wetland restoration, and sustainable agriculture, which naturally absorb carbon in the environment. Technology-based projects, on the other hand, involve investments in new technologies that enhance efficiency or reduce emissions, such as renewable energy projects, energy-efficient initiatives, and waste management solutions.

Compliance carbon markets and the voluntary carbon markets

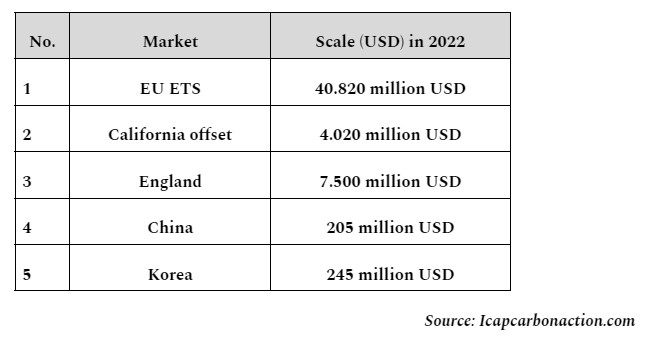

After the Kyoto Protocol and the regulatory frameworks of developed countries (such as Europe, the US, Japan, Australia...), the carbon market has experienced significant growth, with two main types of markets:

1. Compliance carbon markets

The market where carbon trading is based on the commitments of countries under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to achieve greenhouse gas reduction targets. This market is mandatory and primarily focused on projects within the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) or Joint Implementation (JI). Currently, the largest are the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and the United States carbon market (American Carbon Registry). China also has its independent carbon market, which is experiencing rapid growth.

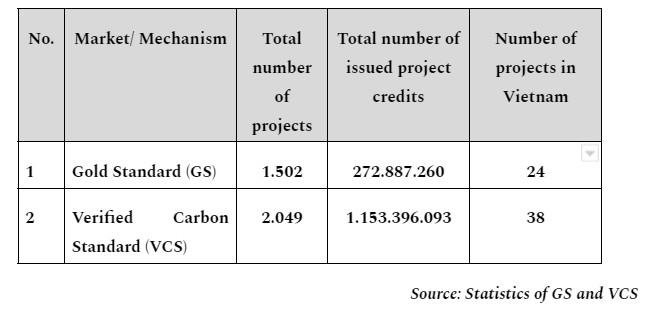

2. Voluntary carbon markets

Based on cooperative agreements between organizations, companies, or countries, the buyer voluntarily participates in transactions to meet environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) policies for carbon footprint reduction. Currently, there are two major voluntary carbon markets: Gold Standard (GS) and Verified Carbon Standard (VCS).

A milestone in the process of international climate policy negotiations is the advent of the Paris Agreement (PA) at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in 2015, considered as a successor to the Kyoto Protocol. However, unlike the Kyoto Protocol, the obligation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is no longer a binding target solely for developed countries. Within the framework of the PA, the goal of "Keeping the global average temperature rise well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C" not only binds Annex I countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but for the first time, non-Annex I countries also have the obligation to set emission reduction targets through Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and implement the emission reduction commitments stated in their NDCs. Along with the establishment of the PA, new market-based mechanisms have been set up in Article 6.2 and 6.4 of this Agreement.

-

Article 6.4 introduces a new mechanism - the Sustainable Development Mechanism (SDM) - aimed at contributing to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and supporting sustainable development on a voluntary basis. Currently, the regulations related to the Article 6 mechanisms are being finalized through negotiation processes in the meetings of the Parties to the Paris Agreement.

At COP26 (2021), Vietnam, along with nearly 150 countries, committed to achieving net-zero emissions by the mid-century; together with over 100 countries, pledged to reduce global methane emissions by 2030 compared to 2010 levels; along with 141 countries, participated in the Glasgow Leaders' Declaration on forests and land use; and joined nearly 50 countries in the global declaration to transition from coal to clean energy. These commitments align with the global trends towards green development, circular economy, digital transformation, and serve as a driving force to transition the economy towards modernization.

As time goes on, an increasing number of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are being signed, and along with it, tariff barriers into major markets (such as EU, US, China, Japan, South Korea, etc.) are being removed. As a result, lawmakers in these countries will enact strict regulations on carbon footprints for imported goods. The most prominent example is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) introduced by the European Union (EU) to prevent EU businesses from relocating carbon-intensive production activities abroad to take advantage of laxer standards, also known as "carbon leakage," by shifting emissions outside of the EU, undermining the EU's and global climate neutrality ambitions.

Essentially, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will impose a carbon tax on all imported goods into EU member countries based on the greenhouse gas emissions intensity in the production process in their country of origin. In the initial phase, CBAM will focus on the most carbon leakage-prone product categories, such as cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, Hydrogen, and Electricity, and will expand to include more goods in the future.

Therefore, it becomes increasingly essential for the Vietnamese government and businesses to grasp, implement domestic carbon market mechanisms, and comply with international standards.

Thus, it can be said that the trend towards sustainable development and climate change adaptation is an inevitable and irreversible direction. Building a domestic carbon market, meeting market standards, and connecting with the international market are crucial and necessary. It is essential to recognize the risks and opportunities in the development of the carbon market in Vietnam.

2. Carbon pricing, valuation tools, and the benefits they bring

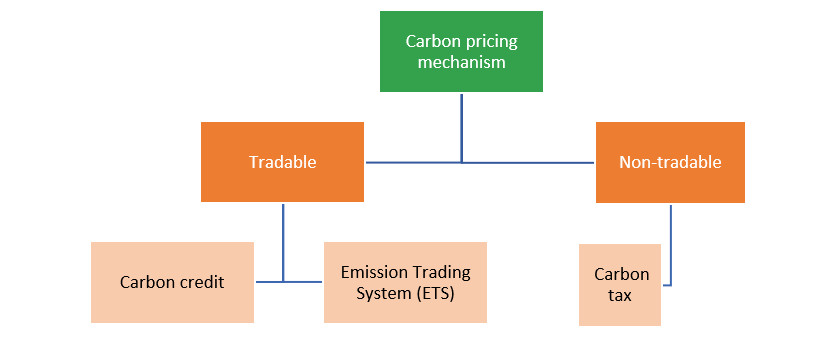

Carbon pricing is a mechanism where the costs and damages caused by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (such as crop loss, healthcare expenses due to extreme weather events, etc.) are evaluated and the burden of these emissions is shifted back to the sources responsible for them. This price is typically set as a price per metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). The main carbon pricing instruments include:

Carbon Tax

The government sets a fixed tax rate that emission sources must pay for each ton of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions they release into the atmosphere. However, unlike the Emission Trading System/Scheme (ETS), the carbon tax is introduced by the government with a fixed price and a clear trajectory for increasing the tax as well as defined rules for adjusting the tax rate. Nevertheless, the emission reduction outcomes of this tool are not predetermined as it does not impose emission limits on the taxed entities.

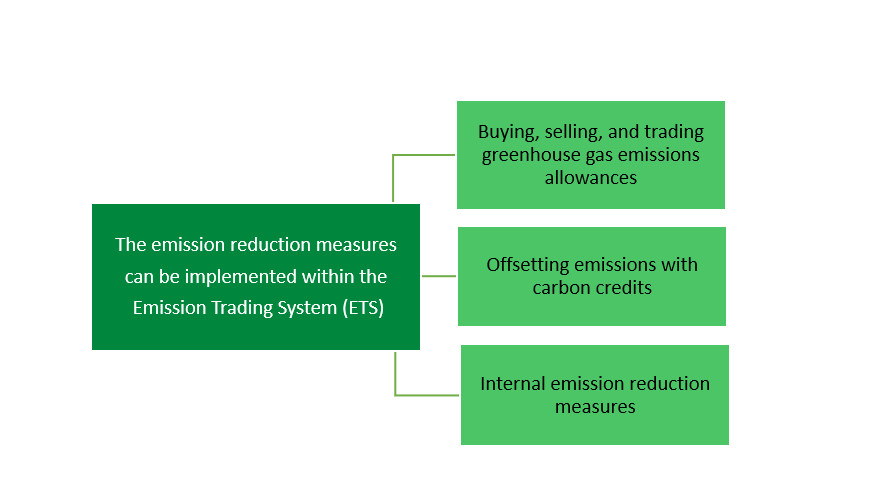

Emission Trading System (ETS)

It is a system established by the government to set emission limits for regulated emission sources under the ETS through the allocation of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission allowances. Emission sources under the ETS are allowed to trade these emission allowances with each other to optimize their emission reduction costs. Additionally, ETS-regulated entities can implement internal emission reduction measures or purchase government-recognized carbon credits to offset their emissions. Non-compliance may result in penalties several times higher than the market price of the emission allowances.

Offsetting Mechanism, Carbon Credit

It is a mechanism where the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) from an activity in a project is quantified according to strict rules and methodologies and used by a country, organization, or emission source to offset its own GHG emissions. This is a flexible mechanism that provides a solution for a country, organization, or emission source to reduce its emissions when the internal emission reduction costs are not optimal

Carbon pricing tools also bring different benefits to different stakeholders in society.

For governments, carbon pricing is one of the key climate policy tools, generating significant revenue from carbon taxes or auctioning emission allowances. With this revenue, governments can invest in research and development of green technologies, support vulnerable communities in adapting to the impacts of climate change, or aid the transition to a low-carbon economy.

For businesses, carbon pricing helps raise awareness of climate risks and enables them to identify sensible transition strategies, thereby enhancing their competitive advantage and creating opportunities for additional revenue streams. For instance, as government commitments lead to scarcity in fossil fuel energy sources or higher prices for emission allowances or carbon credits on the market, businesses can implement energy transition measures in their production processes and develop climate-appropriate strategies. Moreover, if they have a well-thought-out emission reduction strategy, businesses can generate revenue from selling carbon credits or surplus emission allowances.

For long-term investors, carbon pricing helps analyze the impacts of climate change policies on investment portfolios and reallocating capital to low-emission or climate-adaptive activities. Through carbon pricing, investors can assess the costs and benefits of investments and make effective investment decisions.

3. Challenges in the carbon market

Currently, Vietnam does not have a domestic carbon market to support businesses in their sustainable development strategies and participation in global supply chains that require carbon footprint standards. As a result, some businesses may face difficulties in the future when competing to export goods and services to large and high-demand markets (e.g., the textile industry in 2023 facing strong competition from countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan, which have carbon programs for their nations).

As mentioned earlier, major markets around the world have already implemented or will continue to add carbon regulations for imported goods, leading to potential disparities between Vietnam's carbon regulations and those of the global market. This could diminish the competitiveness of Vietnamese businesses and create challenges in their production and supply processes for large customers worldwide.

Most of the carbon credit projects currently issued in Vietnam are voluntary market projects, and project owners often lack a comprehensive understanding of the market. Due to the lack of domestic mechanisms, they often delegate the execution of international carbon credit transactions to international consulting firms, which may result in suboptimal benefits and potential long-term disadvantages due to speculative activities and hoarding by major international carbon trading organizations.

To address these challenges, it is crucial for Vietnam to develop a robust domestic carbon market, harmonize its carbon regulations with international standards, and provide comprehensive support and guidance to local businesses participating in carbon credit projects. This will not only enhance their competitiveness in the global market but also maximize the sustainable development benefits derived from carbon credit initiatives.